Today, when 3D graphics and artificial intelligence increasingly dominate visual production, re-examining the aesthetic significance of 2D animation is not out of nostalgia for tradition, but rather a reaffirmation of the value of an artistic paradigm.

The ultimate charm of images may not lie in the perfect reproduction of reality, but in the unique and individual poetic presentation of the human spiritual world, thereby achieving effective communication from “aesthetic appreciation” to “emotional resonance”.

The domestically produced 2D animated film “Little Monsters of Langlang Mountain,” produced by the Shanghai Animation Film Studio, became a dark horse of the 2025 summer box office, successfully breaking the box office record for domestically produced 2D animation in Chinese film history. The film utilizes 2D hand-drawing, employing traditional Chinese painting techniques such as coloring, line work, modeling, and white space as a core medium for embodying Eastern aesthetics. Its visual strategy explores a dynamic balance between realistic space and freehand charm, narrative functionality and stylistic artistry, and the rawness of modeling and the playfulness of performance. The film’s outstanding performance, both critically and at the box office, prompts us to re-examine the importance of 2D animation in preserving and developing the unique aesthetic style of the Chinese animation school, given the rapid development of 3D and AI imaging technologies.

Animated film “The Little Monsters of Langlang Mountain”

1

The expression of oriental aesthetics in domestic 2D animation is the result of inheriting tradition and bringing forth new things under the ever-changing technological and cultural contexts from the film era to the digital era and then to the current artificial intelligence era.

Looking back at the development of Chinese animation, 2D animations that have achieved a high level of artistic achievement often utilize traditional Chinese techniques and artistic styles to express themselves in a nationalistic manner, showcasing the ingenious integration of traditional Chinese culture and modern animation, and embodying the Chinese understanding of beauty. This expression of Eastern aesthetics in Chinese 2D animation is the result of a continuous commitment to the creative principle of “never repeating oneself, never imitating others,” inheriting tradition while introducing new ideas, from the film era to the digital age, and then to the current era of artificial intelligence. Amidst the rapidly evolving technological and cultural contexts, the 2D animation industry has consistently upheld the principle of “never repeating oneself, never imitating others,” inheriting tradition while simultaneously introducing the new. Take ink-and-wash animation, for example. “The Little Tadpole Looking for His Mother,” China’s first color ink-and-wash animation, debuted in the film era. By filming layered ink paintings separately and then overprinting them color by color, following the principle of “light to dark, pale to thick,” the artist successfully brought Qi Baishi’s ink paintings to life. At a time when 2D animation was primarily based on single-line flat painting, this groundbreaking work expanded the paradigm and boundaries of animation art. The animated short film “Landscape Love” uses the guqin and natural sound effects to complement the landscape, conveying the philosophical concept of “harmony between man and nature” and humanistic sentiment. The film’s interaction with nature and the expression of the teacher-student bond are presented in a way that “words are finite but meaning is infinite,” embodying the classical Chinese aesthetic principle of “integrating emotion into scenery” and “using scenery to express emotion.”

Animated short film “Mountain and Water Love”

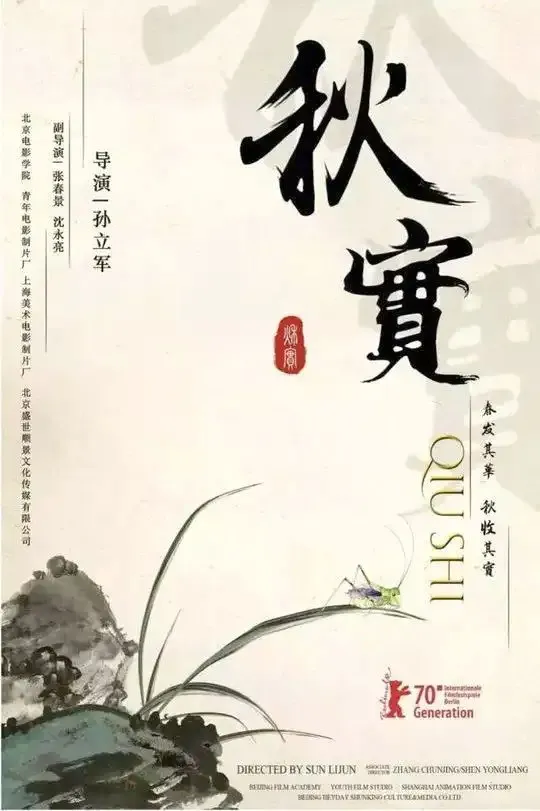

Although the advent of the digital age has promoted the vigorous development of 3D animation technology and 2D hand-drawn animation has entered the “paperless” era, local creators still insist on exploring the boundaries of 2D animation in spatial interpretation in a new technological context. For example, the digital ink animation short film “Pond” released in 2006, through the use of models, textures and materials in 3D software, simulates the composition paradigm of traditional ink painting and the visual texture of ink smudged on rice paper; in 2020, the world’s first 8K ink animation “Autumn Harvest” was shortlisted for the New Generation Unit of the 70th Berlin Film Festival. The film cleverly combines 8K ultra-high-definition display technology with Mr. Qi Baishi’s “both craftsmanship and freehand” painting technique to present the delicate and soft, real and illusory beauty of ink smudges with an accuracy beyond the human eye’s recognition; in 2021, in the sequel “Beginning of Autumn”, the creative team further explored the possibility of using ink elements to build a three-dimensional space through textures and modeling, and to cooperate with lens movement and scene scheduling to create a scene and convey emotions. At the end of the film, the imagination of the relationship between “inorganic life” and “living body” was incorporated. This imagination has a clever intertextuality with the human-computer collaborative relationship in artistic creation in the era of artificial intelligence.

Poster of the ink-and-wash animation “Autumn Harvest”

Since OpenAI launched ChatGPT in November 2022, AI has increasingly achieved remarkable feats in image and video generation, even surpassing the visually immersive “real.” In 2025, coinciding with the centennial of the birth of Chinese ink artist Huang Zhou, the ink art short film “Loess Slope” was released. The creative team not only recreates Huang Zhou’s iconic image of the “little donkey,” but also explores strategies for reconstructing Chinese vernacular ink imagery through generative artificial intelligence (AIGC) technology. This allows them to construct a captivating and immersive virtual space while also capturing the minimalist beauty of blank spaces found in classical Chinese painting. Within the context of AI, the film avoids the techno-centric vortex of “showmanship” and “hyper-realism,” upholding and promoting classical Chinese aesthetics, exploring the oriental poetic and freehand spirit of two-dimensional animation.

Poster for the ink-and-wash animation short film “Loess Slope”

2

The aesthetic value and media characteristics of 2D animation do not lie in the “simulation” of reality, but in “expression”, and more importantly, in the combination of painting language and film language.

The rapid technological evolution of the digital age, particularly the widespread adoption of 3D animation, once pushed 2D animation to the brink of being “traditional” or even “obsolete.” 3D technology, with its precise simulation of the physical world, efficient rendering capabilities, and industrialized production processes, dominated the mainstream commercial animation market. Now, the emergence of AIGC, with its powerful image generation and style transfer capabilities, seems to herald a more radical and fundamental disruption. Its ability to learn, imitate, and generate dynamic images at unprecedented speeds poses a fundamental challenge to 2D animation, which is centered around “frame-by-frame drawing.” However, this assertion largely overlooks the ontological foundations of 2D animation. As an art form that “creates dreams with the tip of the pen,” its aesthetic value and medium characteristics lie not in its “simulation” of reality but in its “expression,” and more importantly, in the fusion of pictorial and cinematic language.

Painting focuses on visual expression in static space, specifically how composition, color, light and shadow, line, and texture convey beauty, emotion, and information within a single frame. Film language, on the other hand, focuses on audiovisual narratives in dynamic time. Through the interplay of camera angles, camera movement, editing, and sound, the interplay of frames tells stories and conveys meaning. Compared to live-action images and even 3D images using motion capture technology, 2D animation is distinguished by its inherent hypothetical nature. This allows for a great degree of spatiotemporal flexibility between frames and a multitude of possible interplays. Together, these two factors contribute to the multifaceted nature of the “painting follows shadow” paradigm. The speed and pauses of an action are determined by the density of the painted frames. This meticulous control of time is a highly artistic “sculpting” process. This allows 2D animation to retain the timeless beauty of painting while retaining the allure of cinematic narrative. For example, in the animated film “Havoc in Heaven,” when depicting Sun Wukong’s high-altitude leaps, the creators focused on the accumulation of energy during his jumps, emphasizing the size of his strides while downplaying the effort during his transitions, to create a sense of lightness and grace. This poetic portrayal, from momentum to dynamics, builds on the monkey’s animality to vividly showcase its “supernatural” divinity, granting the performance of two-dimensional animated characters an infinite space for imagination that transcends the paradigm of real-world experience, leading viewers into a fictional world created from nothing, emphasizing symbolism over simulation. This shows that the hypothetical and abstract nature of two-dimensional animation, to a large extent, provides more possibilities for exploring the boundless realm of the human spiritual world.

3

The emotions and warmth contained in the “author’s handwriting” of 2D animation have the expressive function of “moving people invisibly”, which can better achieve international communication.

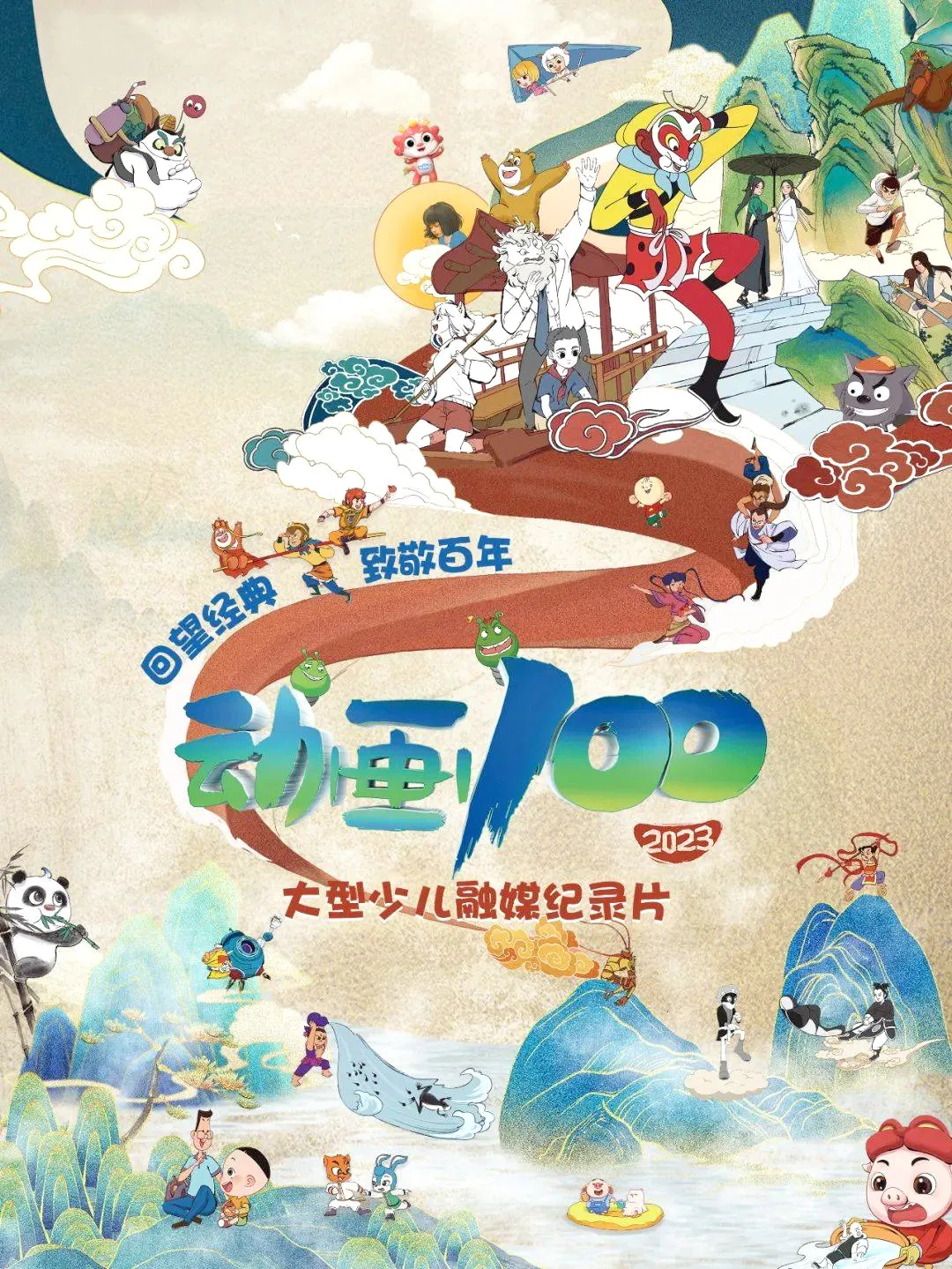

Back in the 1980s, the Chinese animation school enjoyed global acclaim for its distinctive aesthetic style. At the dawn of the new century, after a period of imitation, assimilation, and loss of direction, contemporary Chinese animation has shown a return to its cultural roots, actively exploring ways and methods to transform and reconstruct China’s finest traditional culture within the context of cutting-edge technology, presenting it to the world with a fresh outlook. Successful examples such as the animated films “Nezha: The Devil Child Comes into the World” and “The Legend of Luo Xiaohei,” the animated series “Chinese Tales,” the animated shorts “Autumn Harvest” and “The Beginning of Autumn,” and the animated documentary “100 Years of Chinese Animation”—all widely disseminated at international animation festivals and exhibitions—demonstrate the immense potential of excellent animated films, guided by Eastern wonders and rooted in shared human emotions, to showcase Chinese aesthetics, disseminate Chinese voices, and embody Chinese character. Two-dimensional animation originates from the essential characteristics of hand-drawing, which enables it to retain the rough, original and simple visual experience of traditional art to the greatest extent. The emotion and warmth contained in this “author’s handwriting” has the expressive function of “moving people in the invisible” and can convey the concept of the coexistence of virtuality and reality, and the combination of form and spirit in Eastern philosophy in a more free and diverse manner.

Animated documentary “100 Years of Chinese Animation”

Whimsy, warmth, and emotion are key to an animated work’s resonant impact. 2D animation, at the level of media ontology, provides the perfect environment for the ultimate expression of these three qualities. Its whimsy stems from the boundless creative space between frames; its warmth is reflected in the impromptu brushstrokes and textures within each frame; and its emotion lies in generations of animators’ unwavering commitment to the creative principle of “never repeating oneself, never imitating others.” Therefore, in an era where 3D graphics and artificial intelligence increasingly dominate visual production, re-examining the aesthetic significance of 2D animation stems not from a nostalgic yearning for tradition but rather from a reaffirmation of the value of an artistic paradigm. The return of 2D animation to the forefront of theatrical cinema reminds us, to some extent, that the ultimate allure of the image lies not in a perfect reproduction of reality, but in a unique and individual poetic representation of the human spirit, thereby effectively communicating the value of both aesthetic appreciation and emotional resonance.

(The author is the president of the China Animation Research Institute)

Exploring New Paths Between "Looking Back" and "Looking Forward": An Observation of the 2025 Summer Domestic Animated Films

Exploring New Paths Between "Looking Back" and "Looking Forward": An Observation of the 2025 Summer Domestic Animated Films